The collection of signatures for petitions is a long and arduous one, but in Maine it pays off. When people disagree with laws promoted by the the Legislature, they have an opportunity to reject them through a people's veto. Although this is not a common occurrence, two people's vetoes may go through this year. The article below gives historical context and outlines the necessary processes to achieve democratic change of law in Maine. -Editor

The collection of signatures for petitions is a long and arduous one, but in Maine it pays off. When people disagree with laws promoted by the the Legislature, they have an opportunity to reject them through a people's veto. Although this is not a common occurrence, two people's vetoes may go through this year. The article below gives historical context and outlines the necessary processes to achieve democratic change of law in Maine. -Editor

History doesn't favor 'people's veto'

BY PAUL CARRIER

Blethen Maine Newspapers

Source: http://kennebecjournal.mainetoday.com/news/local/5114501.html

AUGUSTA -- The activists who want Maine voters to overturn two newly passed state laws have about a 50-50 chance of prevailing at the polls, if they can first overcome the difficult task of collecting enough signatures to place their "people's veto" referendums on the Nov. 4 ballot.

When voters get a chance to kill controversial laws passed by the Legislature, they do so only about half of the time, according to state records going back almost 100 years.

But most veto campaigns never make it that far, records show, so the biggest hurdle for veto backers is qualifying for a spot on the ballot.

The people's veto is making headlines these days because two unrelated groups are circulating petitions to try to get voters to repeal new laws.

If both groups succeed to placing their plans on the ballot, it will mark the first time since 1940 that Maine voters have tackled two people's vetoes in one year.

One campaign wants to block legislatively approved taxes on beer, wine and soda to help pay for the Dirigo Health program.

The other one wants to repeal a state law that would tighten procedures for issuing Maine driver's licenses, in part by requiring that applicants prove they are in the country legally.

Both campaigns involve a long-established but seldom-used provision in the Maine Constitution that allows voters to repeal, or veto, laws passed by the Legislature.

The provision is very similar to another constitutional safeguard that allows Maine voters to pass laws at the ballot box through the initiated referendum.

"It brings a certain legitimacy to the entire (political) process if people participate in it" by second-guessing the Legislature's decisions from time to time, said Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap. "I think it's a good protection to have."

The organizers of each people's veto campaign must collect the signatures of 55,087 voters and submit them to the Secretary of State's Office by July 17 to get their proposal on the ballot this November.

Each camp received permission to start circulating petitions in mid-May, effectively giving them only two months to meet the signature deadline.

If either group succeeds in getting its question on the ballot, the affected law -- new taxes in one case, and new licensing procedures in the other -- would not take effect unless the voters upheld it Nov. 4.

Maine is one of 24 states in the nation, and one of only two in New England, that allow voters to veto newly passed laws, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. But getting a people's veto on the ballot here can be a daunting task, both because of the number of signatures required and the speed with which they must be collected.

Eleven people's veto campaigns have been launched in Maine from 1996 to 2007, for example, but only two of those have actually made it onto the ballot. In the rest of the cases, organizers either abandoned their campaigns before the deadline for submitting petitions to the state, or failed to collect enough valid signatures to force a public vote.

State records show that Mainers have tackled people's veto referendums only 25 times since Sept. 12, 1910, when they vetoed a law setting a uniform standard for the amount of alcohol in liquor. The records also show that voters have not overwhelmingly supported or opposed the laws they were asked to veto. In fact, they have split down the middle since that first vote back in 1910 by upholding 13 laws and killing 12 others.

In the most recent decision, which occurred in 2005, Mainers voted 55 percent to 45 percent to uphold a gay rights law passed by the Legislature that year. By doing so, they reversed a 1998 vote -- the only people's veto referendum of the 1990s -- in which voters vetoed a gay rights law by a vote of 51 percent to 49 percent.

The Christian Civic League of Maine has mounted a referendum campaign this year to repeal various safeguards for gay men and lesbians, but that effort is not a people's veto. It seeks to rescind laws and programs that are in effect already, rather than veto brand-new laws that have yet to take effect.

Although recent people's vetoes dealing with gay rights have had a high profile, the process of asking voters to veto state laws proved much more popular in the early years of the 20th century than in more recent years, according to state records. They show that voters considered four to six vetoes per decade in the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s and three in the 1940s, followed by only one per decade since the 1950s. The fact that there have been relatively few veto referendums over the years, and with mixed results, prompts supporters of the process to argue that it is being used judiciously and that voters are cautious in secondguessing the Legislature. "It's the sort of thing that I think works best when it's used infrequently,"said James Melcher, a political scientist at the University of Maine at Farmington. "I don't think it's gotten too far out of balance." "It's really not being used that much," said Kathleen McGee of Bowdoinham, a leader of the people's veto campaign dealing with driver's licenses. It will be difficult to get that proposal on the ballot, McGee said, because organizers have only two months to collect 55,087 signatures. Critics counter that allowing voters to veto laws gives them more power than they need and undermines the republican form of government. Under such a system, voters elect decision makers to represent them instead of calling the shots themselves, as they would in a direct democracy. "There is a mechanism in place for registering disfavor and changing policy, and that is elections," said Mark Brewer, a political scientist at the University of Maine. In his view, allowing voters to veto laws is unnecessary because voters already have the power to replace politicians who enact offensive laws, by voting them out of office. "The form we set up is inherently a republican form," Brewer said. He said politicians have more time and resources to carefully study issues than the voters do, so lawmakers develop "a more informed position" on issues as a result. "Anything that undermines that makes me a little nervous," Brewer said. Whatever the perceived merits or deficiencies of the process, the two people's veto campaigns can be expected to intensify on June 10, when members of the Democratic, Republican and Green Independent parties cast ballots in primary elections. By law, petition circulators can collect signatures at polling places, so the primaries will provide an ideal forum for doing just that as the July 17 filing deadline approaches.

AUGUSTA -- The activists who want Maine voters to overturn two newly passed state laws have about a 50-50 chance of prevailing at the polls, if they can first overcome the difficult task of collecting enough signatures to place their "people's veto" referendums on the Nov. 4 ballot.

When voters get a chance to kill controversial laws passed by the Legislature, they do so only about half of the time, according to state records going back almost 100 years.

But most veto campaigns never make it that far, records show, so the biggest hurdle for veto backers is qualifying for a spot on the ballot.

The people's veto is making headlines these days because two unrelated groups are circulating petitions to try to get voters to repeal new laws.

If both groups succeed to placing their plans on the ballot, it will mark the first time since 1940 that Maine voters have tackled two people's vetoes in one year.

One campaign wants to block legislatively approved taxes on beer, wine and soda to help pay for the Dirigo Health program.

The other one wants to repeal a state law that would tighten procedures for issuing Maine driver's licenses, in part by requiring that applicants prove they are in the country legally.

Both campaigns involve a long-established but seldom-used provision in the Maine Constitution that allows voters to repeal, or veto, laws passed by the Legislature.

The provision is very similar to another constitutional safeguard that allows Maine voters to pass laws at the ballot box through the initiated referendum.

"It brings a certain legitimacy to the entire (political) process if people participate in it" by second-guessing the Legislature's decisions from time to time, said Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap. "I think it's a good protection to have."

The organizers of each people's veto campaign must collect the signatures of 55,087 voters and submit them to the Secretary of State's Office by July 17 to get their proposal on the ballot this November.

Each camp received permission to start circulating petitions in mid-May, effectively giving them only two months to meet the signature deadline.

If either group succeeds in getting its question on the ballot, the affected law -- new taxes in one case, and new licensing procedures in the other -- would not take effect unless the voters upheld it Nov. 4.

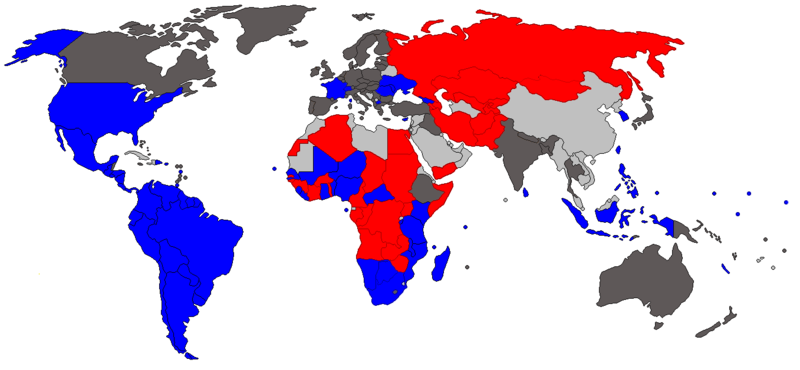

Maine is one of 24 states in the nation, and one of only two in New England, that allow voters to veto newly passed laws, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. But getting a people's veto on the ballot here can be a daunting task, both because of the number of signatures required and the speed with which they must be collected.

Eleven people's veto campaigns have been launched in Maine from 1996 to 2007, for example, but only two of those have actually made it onto the ballot. In the rest of the cases, organizers either abandoned their campaigns before the deadline for submitting petitions to the state, or failed to collect enough valid signatures to force a public vote.

State records show that Mainers have tackled people's veto referendums only 25 times since Sept. 12, 1910, when they vetoed a law setting a uniform standard for the amount of alcohol in liquor. The records also show that voters have not overwhelmingly supported or opposed the laws they were asked to veto. In fact, they have split down the middle since that first vote back in 1910 by upholding 13 laws and killing 12 others.

In the most recent decision, which occurred in 2005, Mainers voted 55 percent to 45 percent to uphold a gay rights law passed by the Legislature that year. By doing so, they reversed a 1998 vote -- the only people's veto referendum of the 1990s -- in which voters vetoed a gay rights law by a vote of 51 percent to 49 percent.

The Christian Civic League of Maine has mounted a referendum campaign this year to repeal various safeguards for gay men and lesbians, but that effort is not a people's veto. It seeks to rescind laws and programs that are in effect already, rather than veto brand-new laws that have yet to take effect.

Although recent people's vetoes dealing with gay rights have had a high profile, the process of asking voters to veto state laws proved much more popular in the early years of the 20th century than in more recent years, according to state records. They show that voters considered four to six vetoes per decade in the 1910s, 1920s and 1930s and three in the 1940s, followed by only one per decade since the 1950s. The fact that there have been relatively few veto referendums over the years, and with mixed results, prompts supporters of the process to argue that it is being used judiciously and that voters are cautious in secondguessing the Legislature. "It's the sort of thing that I think works best when it's used infrequently,"said James Melcher, a political scientist at the University of Maine at Farmington. "I don't think it's gotten too far out of balance." "It's really not being used that much," said Kathleen McGee of Bowdoinham, a leader of the people's veto campaign dealing with driver's licenses. It will be difficult to get that proposal on the ballot, McGee said, because organizers have only two months to collect 55,087 signatures. Critics counter that allowing voters to veto laws gives them more power than they need and undermines the republican form of government. Under such a system, voters elect decision makers to represent them instead of calling the shots themselves, as they would in a direct democracy. "There is a mechanism in place for registering disfavor and changing policy, and that is elections," said Mark Brewer, a political scientist at the University of Maine. In his view, allowing voters to veto laws is unnecessary because voters already have the power to replace politicians who enact offensive laws, by voting them out of office. "The form we set up is inherently a republican form," Brewer said. He said politicians have more time and resources to carefully study issues than the voters do, so lawmakers develop "a more informed position" on issues as a result. "Anything that undermines that makes me a little nervous," Brewer said. Whatever the perceived merits or deficiencies of the process, the two people's veto campaigns can be expected to intensify on June 10, when members of the Democratic, Republican and Green Independent parties cast ballots in primary elections. By law, petition circulators can collect signatures at polling places, so the primaries will provide an ideal forum for doing just that as the July 17 filing deadline approaches.

No comments:

Post a Comment