This article demonstrates some of the reasons why all states should have more opportunities for direct democracy, but it focuses on some specific issues faced in Connecticut. In a harsh tone, Cohen criticizes the initiative and referendum process as being too chaotic. Of course moving toward direct democracy will be sticky because there has to be some rupture with the current state apparatus. Politicians will be reluctant to hand over power to the people, but it is a process that must take place in order to make the most just and democratic system possible. Until we do provoke change within every state, the same people will continue to make decisions regarding our well-being. For more about the constitutional convention, also see: http://www.newamerica.net/blog/blockbuster-democracy/2008/connecticut-next-blockbuster-democracy-frontier-4869 - Editor

This article demonstrates some of the reasons why all states should have more opportunities for direct democracy, but it focuses on some specific issues faced in Connecticut. In a harsh tone, Cohen criticizes the initiative and referendum process as being too chaotic. Of course moving toward direct democracy will be sticky because there has to be some rupture with the current state apparatus. Politicians will be reluctant to hand over power to the people, but it is a process that must take place in order to make the most just and democratic system possible. Until we do provoke change within every state, the same people will continue to make decisions regarding our well-being. For more about the constitutional convention, also see: http://www.newamerica.net/blog/blockbuster-democracy/2008/connecticut-next-blockbuster-democracy-frontier-4869 - Editor

July 4, 2008

In a sissy Northeastern state such as Connecticut, there are dozens of issues considered too icky to be discussed by the General Assembly.

The legislators say a little prayer each night, begging that abortion stuff and same-sex marriage stuff and English-as-the-official-language stuff and anti-affirmative action stuff and lots of other, well, icky stuff never comes up — or at the least, never prompts a public hearing at which the Great Unwashed can go on and on about stuff that is simply too icky to imagine.

On the other end of the legislative agenda are things so obscure that one questions whether the Founding Fathers should have bothered risking their lives to free us from British cuisine. The state flower, the state lizard, the state cantata — the legislators live in fear that some third-grade class will champion such stuff and they will be forced to vote up or down, perhaps being pressured to support the wrong lizard or, in the alternative, crushing the spirit of youngsters participating in the legislative process.

One strategy to relieve all this angst would be to establish an initiative and referendum process at the state level, empowering the citizenry to express themselves directly on all manner of icky and obscure stuff — and thus freeing legislators from the horror of divining the public good.

This November, as we march to the polls to decide once and for all whether Barack Obama is the Messiah or merely a kid with a good speechwriter, we will also vote on whether to hold a constitutional convention in Connecticut, to consider, among other things, an initiative and referendum process that would empower us all to throw off the tyranny of third-graders and pick our own darn state lizard.

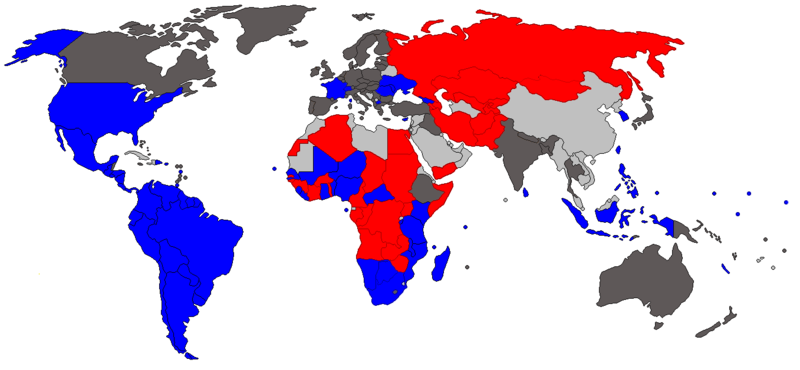

Depending on who is doing the counting and defining the terms, about half the states have some kind of direct-democracy process by which voters can express themselves. South Dakota was the first state to adopt such stuff, in 1893 — and the idea caught on in "progressive" circles as a populist tool to tame the railroad magnates and bankers and newspaper publishers and other stuffy rich people who presumably controlled the state legislatures.

Today, the initiative and referendum process is considered more the tool of conservatives than "progressives" — a process by which the voters can rise up and smack the tax-and-spenders or the trendy social liberals. Although the referendum process is already in place in some Connecticut towns, efforts to establish a system for state government have never gotten very far in the legislature. The boys and girls in Hartford, most of them safe in carefully drawn voting districts that ensure their re-election forever, are happy with the current system, except for the lizard stuff.

The current political and governance environment suggests that Connecticut would be the last state in the union to ever approve a referendum process. With the Democrats in control of the legislature forever, and with voters canny enough to never elect a Democratic governor, the shaky equilibrium offers up slow-and-steady, mildly destructive public policy that fits the bland political personality of the state.

Initiative and referendum suggests uncertainty, instability, encroachment on the powers of the well-connected. If direct democracy ever came to a real vote in Connecticut, even the chamber of commerce types and the business associations that pretend to be grouchy about high taxes would come out against it.

The taxpayer advocacy groups and other fiscal hawks in Connecticut would march in the streets for direct democracy, thus prompting the teachers unions and social-service crybabies to recruit armies of naysayers to protect their tax-and-spend hold on the General Assembly.

If, through some miracle, a referendum system ever did make it onto a ballot for voter consideration, the Connecticut compromise machine would be working overtime. There would be an "emergency" escape clause that would make the referendum decisions toothless — and the petitioning process would be made unnecessarily onerous, so as to discourage all but the most avid fans from launching a tax-cutting orgy of ballot questions.

By the way, Cohen should be named "State Columnist." Think about it. Prepare the petitions. The time is near.

Laurence D. Cohen is a public policy consultant who served as special assistant to former Gov. John G. Rowland. His column appears every other Friday. He can be reached at cohencolumn@aol.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment