The U.S. Media Reform Movement

Going Forward

Going Forward

Robert W. McChesney

Source:http://www.monthlyreview.org/080915mcchesney.php

All social scholarship ultimately is about understanding the world to change it, even if the change we want is to preserve that which we most treasure in the status quo. This is especially and immediately true for political economy of media as a field of study, where research has a direct and important relationship with policies and structures that shape media and communication and influence the course of society. Because of this, too, the political economy of communication has had a direct relationship with policy makers and citizens outside the academy. The work, more than most other areas, cannot survive if it is “academic.” That is why the burgeoning media reform movement in the United States is so important for the field. This is a movement, astonishingly, based almost directly upon core political economic research.

The political economy of media is dedicated to understanding the role of media in societies—e.g., whether the media system on balance encourages or discourages social justice, open governance, and effective participatory democracy. The field also examines how market structures, policies and subsidies, and organizational structures shape and determine the nature of the media system and media content. The entire field is based on the explicit understanding that media systems are not natural or inevitable, but they result from crucial political decisions. These political decisions are not made on a blank slate or a level playing field; they are strongly shaped by the historical and political economic context of any given society at any point in time. We make our own media history, to paraphrase Marx, but not exactly as we please. We do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

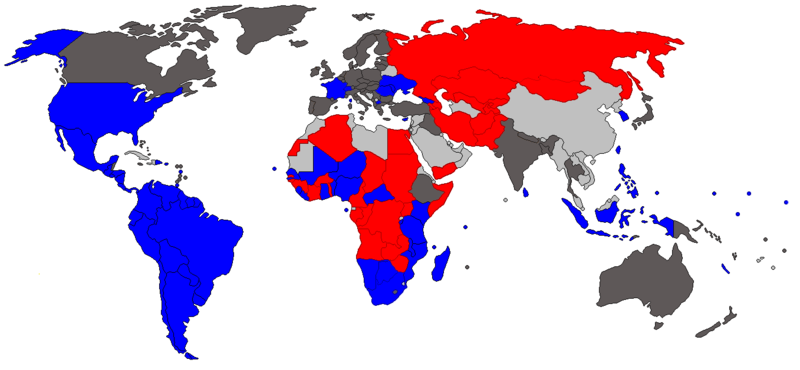

For much of the past century there has been a decided split in the political economy of media between U.S. scholars and those based in almost every other nation in the world. In the United States it generally has been assumed, even by critical scholars devoted to social change, that a profit-driven, advertising-supported corporate media system was the only possible system. The media system reflected the nature of the U.S. political economy, and any serious effort to reform the media system would have to necessarily be part of a revolutionary program to overthrow the capitalist political economy. Since that was considered unrealistic, even preposterous, the structure of the media system was regarded as inviolable. The circumstances existing and transmitted from the past allowed for no alternative.

Elsewhere in the world, capitalism was seen as having a less solid grasp on any given society, and the political economy was seen as more susceptible to radical reform. Every bit as important, media systems were regarded as the results of policies, and subject to dramatic variation even within a capitalist political economy. In such a context it was more readily grasped that the nature of the media system would influence the broader political decisions about what sort of economy a society might have. In other words, the political economy not only shaped the nature of the media system, the nature of the media system shaped the broader political economy. Scholars and activists were more likely to understand that winning battles to reconstruct the media system were a necessary part of a broader process to create a more just society, even if the exact reforms being fought for were not especially revolutionary in their own right

Click here to continue reading.

All social scholarship ultimately is about understanding the world to change it, even if the change we want is to preserve that which we most treasure in the status quo. This is especially and immediately true for political economy of media as a field of study, where research has a direct and important relationship with policies and structures that shape media and communication and influence the course of society. Because of this, too, the political economy of communication has had a direct relationship with policy makers and citizens outside the academy. The work, more than most other areas, cannot survive if it is “academic.” That is why the burgeoning media reform movement in the United States is so important for the field. This is a movement, astonishingly, based almost directly upon core political economic research.

The political economy of media is dedicated to understanding the role of media in societies—e.g., whether the media system on balance encourages or discourages social justice, open governance, and effective participatory democracy. The field also examines how market structures, policies and subsidies, and organizational structures shape and determine the nature of the media system and media content. The entire field is based on the explicit understanding that media systems are not natural or inevitable, but they result from crucial political decisions. These political decisions are not made on a blank slate or a level playing field; they are strongly shaped by the historical and political economic context of any given society at any point in time. We make our own media history, to paraphrase Marx, but not exactly as we please. We do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

For much of the past century there has been a decided split in the political economy of media between U.S. scholars and those based in almost every other nation in the world. In the United States it generally has been assumed, even by critical scholars devoted to social change, that a profit-driven, advertising-supported corporate media system was the only possible system. The media system reflected the nature of the U.S. political economy, and any serious effort to reform the media system would have to necessarily be part of a revolutionary program to overthrow the capitalist political economy. Since that was considered unrealistic, even preposterous, the structure of the media system was regarded as inviolable. The circumstances existing and transmitted from the past allowed for no alternative.

Elsewhere in the world, capitalism was seen as having a less solid grasp on any given society, and the political economy was seen as more susceptible to radical reform. Every bit as important, media systems were regarded as the results of policies, and subject to dramatic variation even within a capitalist political economy. In such a context it was more readily grasped that the nature of the media system would influence the broader political decisions about what sort of economy a society might have. In other words, the political economy not only shaped the nature of the media system, the nature of the media system shaped the broader political economy. Scholars and activists were more likely to understand that winning battles to reconstruct the media system were a necessary part of a broader process to create a more just society, even if the exact reforms being fought for were not especially revolutionary in their own right

Click here to continue reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment